How Yukong Moved the Mountains

The highest historical expression of socialism on a mass scale

How Yukong Moved the Mountains is a series of 12 documentary films that covers the Cultural Revolution in China, between 1972 and 1974. It was shot and directed by a dutch filmmaker and his partner.

This is a controversial period of time that is often overlooked, minimized and misrepresented. This film gives us a one-of-a-kind glimpse in the most developed form of socialism that ever existed.

Below is a selection of excerpts from each episode. I was unable to transcribe every part of the documentary due to its length, so for a fuller picture of what life in China was like during this period, I highly recommend watching it.

It's a long watch, so that's why I made this little project, to try and make its contents a little more accessible. I hope to add onto this overtime, as I revisit each section and find bits I'd like to include here.

Currently, this film in its entirety is available on YouTube for free.

In the event the film is ever removed from YouTube or if that link dies, the entire film is also available on on Archive.org here. I have also archived this copy so if that link ever goes down, reach out to me at sadgrl@riseup.net and I can send you a copy.

I am working on adding excerpts from each of the listed sections.01 - The Fishing Village

Watch The Fishing Village on YouTube [1:36:11]

This section focuses on a small fishing village in China.

Narrator: We’re spending the month of June in the village of Kao Yudao (?). In English this means ‘big fish village’. 5,500 people live here. The village has 263 boats used for both coastal and deep-sea fishing.

The province of Shantung (?) is a quarter the size of the state of Texas and it has 64 million inhabitants. It’s shores stretch for more than a thousand miles. Shantung lies between northern and southern China. It is also the birthplace of Confuscious.

All boats are owned collectively by the brigade. Once a year they hold a meeting to decide whether they need to buy new boats from the state. Fishermen do not sell their catch privately; everything is sold to the state.

A few years ago, fishermen were paid according to a quota system. Those who caught less than a certain amount had their salaries docked. Those who caught more received bonuses. On the whole, the community was poor and stagnating except for a few rich individuals. During the cultural revolution, the village went through a major upheaval. The brigade’s leadership was changed. Today, the fisherman are paid according to a system of work points they have established themselves.

Chairman Interview

In this interview, we are introduced to the chairman of the village's Revolutionary Committee and his daughters.

Chairman: At first I was disappointed… later on, I understood men and women are equal.

Interviewer: Did you go to school when you were young?

Chairman: Since I was born in the old society and my family was very poor, I couldn’t go to school. I learned in the People’s Liberation Army. We all studied together and the leaders helped. Now I know how to read and write.

Interviewer: You’re the chairman of the Revolutionary Committee. How are you paid?

Chairman: Even though I’m in charge, we’re all equal. I earn points according to the work I do.

Interviewer: Is your salary higher than the fishermen?

Chairman: No, since I work a little less than the fisherman, I earn less than they do. Twice a year, we discuss the distribution of work points. Each person proposes their own salary and everyone discusses it. Sometimes people ask for more than they deserve.

Interviewer: Do you really practice democracy in the brigade?

Chairman: In our brigade, the cadres must consult the people before making a decision. For instance, when a problem comes up, cadres consult the workers. They exchange opinions. The discussion goes from the workers, back to the workers, many times. Decisions made unanimously carry more weight. In all, there are more than 1,200 families. Our production brigade is quite large. To improve the standard of living, we also have a nursery, a kindergarten, a public bath, a clubhouse, a reading room, and a sports field.

Doctor Interview

In this interview, we meet with a doctor at the village's clinic.

Interviewer: In your opinion, why did Chairman Mao say, at the beginning of the

Cultural Revolution, that doctors were like lords in the big cities?

Doctor: The city doctors thought they were above it all. They didn’t care about

peasants like us. When we went for a consultation, the doctors treated us slightly and weren’t very

helpful. That’s why we didn’t like them very much. Now the city doctors help us a lot. Sometimes they

come to the country with knapsacks full of medicine and instruments. They come to pay house calls so the

peasants really like them now. They also do minor surgery on the spot.

Interviewer: Can you tell us what the barefoot doctors are?

Doctor: Our country has a large population. The rural regions, especially the more

remote ones, need doctors in medicine. The hospitals alone can’t take care of all of the patients. We

asked for help from the high school students who are good workers and very willing. After they finish

school, they spend time doing manual work and then they come here. We send them to the local hospital as

apprentices, and then they come back here again to practice work. At the same time, they study and

improve their professional skills. Even though they haven’t been to medical school, they take care of

the rural population wholeheartedly, and they’re welcome everywhere. After a while, we send them back to

the hospital again to perfect their skills. Now medical care is more accessible to the peasants in our

brigade. Common illnesses are treated on the spot.

02 - A Barracks

Watch A Barracks on YouTube [00:52:33]

This section covers daily life in the army's military barracks.

Narrator: This is the base of the 337th artillery regiment 179th division Nanking regiment. We lived in a room here for several weeks. This way, we observed the daily activities of the company.

Interview with the Commander

Commander: I'm the commander of this regiment. My name is Wu Hi Hi. I enlisted in 1953. I'm from a poor peasant family. There are five people in my family: three children and my wife. My wife works in a soap factory. I live with the deputy commander.

[...]

As for becoming an officer, the best men are chosen from the ranks by their fellow soldiers. We discuss the candidates in our party group, and the party committee approves the choice. That's how you become an officer.

Interviewer: Are there any military schools?

Commander: There are military schools, but they're not so important. They're mostly used to help the officers become more competent and improve their skills. For the most part, officers are trained in the field.

Interviewer: How is the workweek organized?

Commander: Each week, we have four days of military training, one day of political studies, half a day for the party activities, and half a day for the Youth League. Saturday afternoon is for the Youth League activities. Time is allotted for the company's needs too, for example, for growing crops or catching up on a class.

Narrator: Once a week, squad leaders and the officers have a meeting.

Soldier: I've summarized the comments my squad made yesterday about the company officers. Now I'll explain them here. There are three points. First, about our company commander: he's not struct enough about our company regulations, more specifically, the routine cleaning of weapons is routinely overlooked. Also, we're not careful enough about the way the mess hall is run. We've started to notice that we've been wasting food. We waste a little every day, and in a year this adds up to a lot of food. If everyone wasted food like this, it would be disastrous. Commanders should be more strict about this. Our commander has a strong sense of responsibility. He's very demanding and quite strict during training. His criticisms aren't always right, and he's sometimes over-critical. For example, some of the new recruits aren't in shape yet. They need practice. Instead of making ineffective criticisms, the commander should help them by pointing out their weaknesses.

04 - Generator Factory

Watch The Generator Factory on YouTube [02:01:10]

This section explores an extremely ordinary factory.

A worker discusses the punch card system which is no longer in use. He explains that before the cultural revolution, everyone had to punch in on arrival and then again when they left.

Worker #1: Any lateness was penalized. If it happened more than once, you would lose your bonus, your salary could be lowered - everything was put in terms of money. No one believed in our political consciousness. It was a way of dividing the workers. We don't punch in anymore. Everyone is conscienscious. There are only a few who arrive late, and they just explain why. [...] You just tell your comrades what happened. Everything is explained and that's the end of it.

Worker #2: There are still some workers that lack discipline. We have to try and educate them patiently. We try to convince them.

Worker #3: Since the Cultural Revolution, we take our work more seriously. We've progressed ideologically, and our consciousness is higher. People are seldom late now, and show a lot of initiative, so our production has increased considerably.

Worker #4: If you have confidence in the workers, they'll show initiative, but if you don't trust them, they'll lose interest in their work.

Interviewer: How do you establish production standards?

Worker: We used to use a stopwatch to calculate the time needed to make each part. We thought this was a scientific method. We’ve done away with these methods. The production schedule used to be decided by a small minority, and now the workers set it up themselves. [ . . .] Before, there were jobs we couldn’t finish on time, and now with our new standards, our production has increased.

Narrator: Jing and Huang (sp?) are two officials in charge of running a generator factory. We met them at an exhibitiation on the Paris Commune.

Jing: A factory must be run by everyone together, not by a few officials. The workers help run the entire factory from general administration down to each workshop and group. They also take part in the leadership of the Revolutionary Committee, and of the party committee.

Huang: The workers actually run the factory themselves and make all of the important decisions.

[...]

Jing: Before making any decisions, the Party Committee must consult the workers. We listen and discuss. Whenever our opinions conflict, we ask the workers for advice. This way, the management staff and the workers can always come to an agreement.

Narrator: Before deciding to film the generator factory, we visited a Steel Mill, a tractor factory, a shipyard and a watch factory. In all, fourteen factories. Some were well-known for having played an outstanding role in the Cultural Revolution, but they weren't what we were looking for. We chose the generator factory because it had no special recommendation. It is just an ordinary factory.

Twice a day at 10:00 in the morning and 4:00 in the afternoon, the factory comes to a halt. For 20 minutes, the workers find many different ways of using the rest period.

The factory has its own medical center and each workshop has a first-aid station. The doctors not only take care of on-the-job injuries, but also the general health needs of the workers and their families. One day a week, the doctors and nurses work at the machines.

[...]

Some of the workers live in Shanghai, 20 miles away. Many of them prefer to go home only on weekends. During the week, they live in a building on the factory grounds. Workers and cadres share rooms from 6 to 8 people.

Work starts here at 7:30 in the morning and ends at 5:00 in the afternoon. It's the same as in most other factories. In addition to the two daily breaks, work stops for lunch between 11:30 and 1:00. The factory employs more than 8,000 people.

Huang: Since we’ve become managers, we’ve often been temped to sit back and relax, work less, and spend more time in the offices than with the workers.

Jing: If you stop manual work, you forget what it’s like to be a worker. Besides, we must stay in close contact with the workers to really understand all of the production problems. Our presence gives the workers a chance to tell us what's bothering them, and to criticize our weak points. It's very important in changing our ideas and in our work.

05 - The Story of the Ball

This section takes us to a school and gives us an idea of how conflict is handledWatch The Story of the Ball on YouTube [17:41]

A group of school children face a conflict at school. At the beginning of the interview, the children are asked about the nature of the problem.

Student: We were playing soccer, but the teacher wanted us to stop since it was after 7am. A ball was right in front of me, so I kicked it. The ball hit the teacher. It wasn't aimed at her; I didn't do it on purpose.

She took me to her office and criticized me, and the teacher took the ball away from everybody just to punish one person. The teacher already criticized me previously about something else, so she probably was looking for another reason to do it again."

Interviewer: Will the student who kicked the ball be punished?

Teacher: No, no punishment. We'll deal with it politically, that's all. We used to punish them by making them stand in a corner, or sending them out of class. We would call their parents and even expel them. We don't do that anymore. Teachers and students are equals now. The problem itself isn't so serious; what's serious is that he defends himself when he knows he's wrong.

07 - About Petroleum

This section focuses on the oilfields of Northern China

Watch About Petroleum on YouTube [1:17:53]

Narrator: This is one of the drilling crews belonging to an outpost far off in the Northeast, the "Great Northern Desert" as the Chinese call it, the territory is about the size of North Dakota. The area is so vast that no camera can capture where people have come from and where they're going - all roads seem to disappear into the horizon.

[...]

Narrator: Da-shing (sp?) was established in 1960. The first pioneers found only the barren prarie. In winter, the temperatures dropped to 20, even 40 below zero. The short summer is a bright change from the months of ice and gray skies. The wind of the Great Plains blows all year long.

In America, the West was won with killing, plunder and greed. The general law was every man for himself. Da-shing has chosen an entirely different approach. Da-shing is a collective effort, governed by the law of the people. As in all conquests, Da-shing has its heroes. Mama Su-e (sp?) is known all over China.

Interview with a Petroleum Worker's Housewife

Mama Su-e: I came here in 1961. The Great Plains seemed to go on forever. I got the idea that the housewives could organize themselves to clear the land, so we went from door to door asking who wants to take part in the work and who doesn't. If the women answered no, we'd have political discussions with them to get them to participate in clearing and farming the land. At first 25 women signed up, but the day we planned to leave, only 5 showed up. As for the others, one had a child, another a sick relative - it was impossible to get them to come. What could five of us do?

I said 'nobody's ever gone out there, let's go and see for ourselves. The others can come later.' There was nothing alive out there, not a living thing. The grass came up to our waists and there wasn't even a path. As we walked, we had to wade through the tall grass. We set up a simple tent with stakes.

[...]

The next day, we started shoveling. After having cleared an acre of land, General Headquarters sent news that they had mobilizxed some more women, and 18 more housewives arrived, which made 23 women in all, but it was late in the season and shoveling went too slowly. We found a wooden plow and pulled it by hand. The work went faster that way. [...] In 1962, we harvested over 3,000 pounds of soubeans and more than 40,000 pounds of vegetables. We only had a shovel to work with. By 1963, there were more of us, and we were able to farm more land. Little by little, our village is growing this way.

Narrator: Da-shing has none of the capitalist greed usually associated with "black gold". Here, they don't want to destroy nature by taking the oil and leaving the land to be reclaimed by the wind and the desert. They are not only developing their own industry, they are also creating an entire social community which will continue to function after the oil is gone.

The several hundred thousand people who have come to Da-shing want to eliminate the traditional divisions between agriculture and industry, between the country and the city.

Here, instead of destroying nature, man invests in it. Small towns have been built every 15 or 20 miles. Each town is surrounded by four or five villages. When we ask the people who live here who they are, they answer 'neither workers nor peasants, neither city nor country people, a little of each'.

Every small town and its villages forms a complete social unit, supplying all of the necessary services, including radio and weather stations and small factories. The gas they get from the oil wells supplies them with free energy for all of their daily needs.

Interview with the Seamstresses

This section focuses on an interview with seamstresses who come to help the workers repair their clothing.

Seamstress #1: According to metaphysics, material objects are unchangeable, but Mao's philosophy has taught us that things can be transformed into their opposites. That's how rags are turned back into cotton. You discover truth by putting ideas into practice. We started out with the idea that cloth was made of cotton. Then we asked 'if cotton can be transformed into cloth, why can't cloth be turned into cotton again?' Practical experienced proved that it was possible. When we tried to find a way to do this, we sometimes got discouraged, but finally we succeeded in making cotton from cloth. We were really excited.

Seamstress #2: At first our experiments didn't work, but we thought that since these rags were made of cotton fiber, there must be a way to make cotton again from the rags. It's a dialectical process.

We tried seven times before we finally got it. Since 1970, we made three hundred thousand pairs of gloves with only ninety thousand pounds of recycled cotton. Our interest in philosophy keeps growing because we can apply it to concrete situations. It's fascinating and it encourages us to study philosophy.

The Office of Geological Research

Researcher: Up until the 1950s, geologists from the imperialist countries claimed that China had very few oil resources. Their main point was that China was made up of land sediments instead of marine sediments. We weren't taken in by this. Mao explained that in order to see if the theory is correct, you must put it into practice. We found oil in Da-shing, quite a lot of oil, in the sandy clay layers. When you talk about land and marine sediments, you're only looking at things superficially. You need to look more deeply to understand how oil is formed.

The Oilworker's Wives

Woman #1: When Da-shing first started out, there was this contradiction between a lot of people and very little housing. How could we solve this problem? If we only counted on men, the construction would have been too slow. To deal with the situation as fast as possible, we decided to take things into our own hands.

But there were prejudices to overcome from the men, and also from some of the women. Even though we were able to do farm work, we still wouldn't be able to do construction work.

Woman #2: It wasn't just the men who didn't have confidence in us, we underestimated ourselves too. Women can farm the land with hoes, but build houses? on ladders with a load of plaster? And what if we fell from so high up? We were afraid. But we practiced. We carried empty buckets up to the roof.

[...]

Woman #1: We like living here as a group. We can do lots of things. Ever since the women got together, we all help each other out. For example, we take care of women who just had babies.

Older Woman: Before, we were isolated within our families. If something happened, for example, if someone got sick, we couldn't count on anybody for help. Now that we live collectively, our lives have changed. When someone gets sick, the others help. They get the doctor to come and treat them. It's a good thing.

Woman #2: Before, it was each family for itself. But living collectively doesn't mean we don't have family life. Each family decides for itself who does the errands or how to furnish the house. At the beginning, we weren't used to collective life. Now we're used to it.

08 - Impressions of a City: Shanghai

Watch Impressions of a City: Shanghai on YouTube [00:55:24]

This section shows what life is like in Shanghai.

Narrator: The buildings in the central city are a reminder of the days of Imperialism. The city is huge. 12 million people live in Greater Shanghai, including the suburban communes administered by the city. Shanghai's responsibilities extend beyond handling its own affairs. The national government delegates some of its responsibilities to large cities like Shanghai. The Departments of Mechanical Industry and Transportation are two of the offices located here.

Hard work is the legacy of past oppression and colonization. That is why Chinese leaders have often declared that China belongs to the third-world, and that the economy is still under development. It is clear that the Chinese must work hard if they want to become economically developed. Working hard means using everything you have, from recycling and repair shops to the development of heavy industry.

Shanghai is a major industrial center. Its 2 million workers are part of a long revolutionary tradition. Zhou Enlai led a great workers' rebellion here in 1927. Forty years later, at the height of the Cultural Revolution, the Shanghai workers again played a decisive role during the intense political struggle. They helped tip the balance toward the left.

Interview with Policemen

This section interviews two policemen whose focus is mainly traffic control.

Policeman #1: Our two main responsibilities concern traffic regulation. The first is our accident prevention program, and the other is on-the-spot traffic control.

Policeman #2: As my comrade just said, we go to the workgroups and factories, organizations and schools to give out information. Our job is to explain things clearly. We use a blackboard and we post up dazibaos, which are handwritten wall-posters. We write out the traffic regulations and give examples of actual accidents, in order to explain how they happened, and to learn from them.

The important thing is to educate the drivers and the bicycle riders in the spirit of socialism. We pay special attention to the way people relate. We do our work with this in mind. The most important thing is for people to care about each other and help each other out. That's why, even if someone breaks a rule, I can let him go on his way.

In general, people do care about each other and respect each other. It's very important to have safe streets. For the most part, rules are welcome but there are some people who don't obey the rules, because their consciousness is low, or because it's too inconvenient. That's why we emphasize people's attitudes toward each other.

You can see for yourself that the street’s been taken over by pedestrians, and that the bicycle riders and drivers don’t always stay in the right lane. That’s why we work on people’s concern for one another. If a pedestrian walks in the street, and not on the crosswalk, the cars will still have to give him the right-of-way to avoid an accident. Just because someone breaks a rule doesn’t mean you have the right to run him over. You can’t do that. That’s why we work on improving people’s respect and concern for others.

Policeman #1: You may have seen in our streets a situation in which the people themselves took part in criticizing the offenders to make them aware of their mistakes. Let's say we're dealing with the problem and the people in the streets don't agree with us. They say what they think about it, and if it's valid, we try to take it into account and reevaluate our positions. If what they say isn't helpful, well, then someone else will help us out.

Narrator: In the old foreign concession, the once famous brothels of Shanghai no longer exist. When we asked the British naval officer what he does nowadays when he stops over in Shanghai, he replied 'I eat in restaurants, I visit exhibits, and I go to the zoo.'

A ride in one of the three-wheeled taxis made here in Shanghai costs only a few cents. The practice of tipping no longer exists. We spoke with one young driver who didn't even know the meaning of the word "tip".

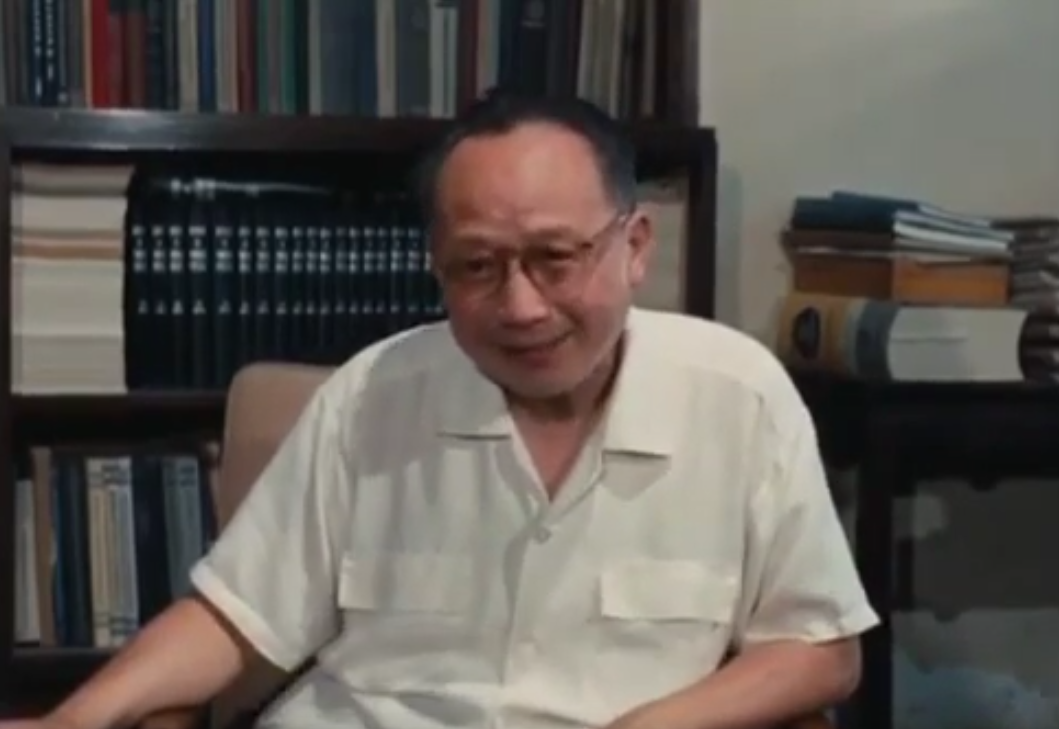

09 - Professor Tsien

This short section is an interview with a science professor.Watch Professor Tsien on YouTube [00:11:09]

Professor's Daughter: When Papa used to come home, he didn't look at anything except his books.

Professor: In those days, I believed the American and Soviet educational systems should be our models, so I thought the best thing for our university was to imitate the most famous American and Russian univerisities. The main characteristic of these universities as a professor is that the professors have all of the power. As a science professor, I held that since Sciences were taught one way in both the US and Russia, we had to do things the same way here. In the past, I treated knowledge like merchandise to be sold to students, and I sold a lot of it. I did all the talking in my classes. I talked but no one got much out of it. Although I only taught science courses, even my scientific explanations were biased by my worldview.

For example, I always placed the most emphasis on theory, by insisting upon theory, because I thought concrete applications were not that important. And because I didn’t stress the practical side of things, my students looked down upon the real world. I told them ‘just learn what I’m teaching you and I guarantee you your theses will be good’. Their only goal was to write a thesis, but studying Mao Tse-tung’s thought raised their consciousness, so they thought I was really difficult to deal with. The whole university called me ‘the helpless case’. I spent about twenty years like that at the university.

At a Western university, my situation might seem normal, but here in a socialist society, people's consciousness is so high that my behavior was unacceptable.

That's why, in the Cultural Revolution, there was a real explosion against me. From the first day, the walls outside were plastered with political posters as soon as they opened the doors. That's all I saw.

Then the Red Guards came to the house saying, 'we'd like to see if you have any reactionary books'. They saw I did have many books, including foreign books, scientific books, and books on mathematics. They didn't think these books were reactionary but they asked me 'In what way do these books contribute to the economic and scientific development of our country?' And since clearly they didn't contribute to it directly, the Red Guard said that they weren't really necessary - although for me, they were all treasures.

So we had different ideas on this, but they were nice about it. They didn't insist at all that my books should be thrown away. They just asked me to think about how many of these books met the needs of the working class.

I thought about this question a lot. It made a profound impact on me.

Professor's Wife: We agreed completely with the Red Guards. They pushed him to change his thinking.

Professor: At the time, the far-left implied that intellectuals like myself would have to leave the univeristy, would be kicked out to go work in the countryside. I told myself, I'm almost 60 years old, too old for that. If I have to go work in the fields, I won't make enough to live on.

I felt sorry for myself and that was all that mattered. This shows that up until then, it spite of some self-awareness, I was still basically selfish. I was very pessimistic. I heard there were rumors that I'd hung myself, but I didn't commit suicide, I lived through it all.

And, well, I thought that, since liberation, China had become a great country which was rapidly

developing. I really wanted to see my country progress and I really didn't want to kill myself.

[...]

In those days, I wrote a lot of articles, and several books too. It was signing my name that motivated me to continue writing. Each one of my publications glorified my name - on the other hand, workers never think of signing their names to the things they make. It doesn't even cross their minds.

Professor: I have one son. He went to work in a factory after he finished high school. He's been there for more than 10 years. He didn't want to attend University. This was a great loss for me. It was inconcievable that my son would never go to college and would be a worker instead. Only later did I come to understand that he'd chosen a better path than I had. I had taken the road of an elite intellectual. Even after he'd become a worker, I kept trying to convince him to go to college, but he didn't have the lease desire to do so.

For a long time, our relationship was strained. But then I changed, and I finally gave my son the respect he deserves.

Professor's Wife: There used to be great differences in our thinking. For example, my husband was angry with our son for having discontinued his studies, but the girls and I supported him.

It was at the factory where he realized his theories didn't amount to much. The professor goes on to tell the story of how Mao encouraged intellectuals to take part in the life of an ordinary worker, in order to educate themselves through manual work. He tells about how the factory was closely connected to the theory of physics that he studied. He found that, while performing a task, his theory wasn't enough to figure out how the task was actually performed.

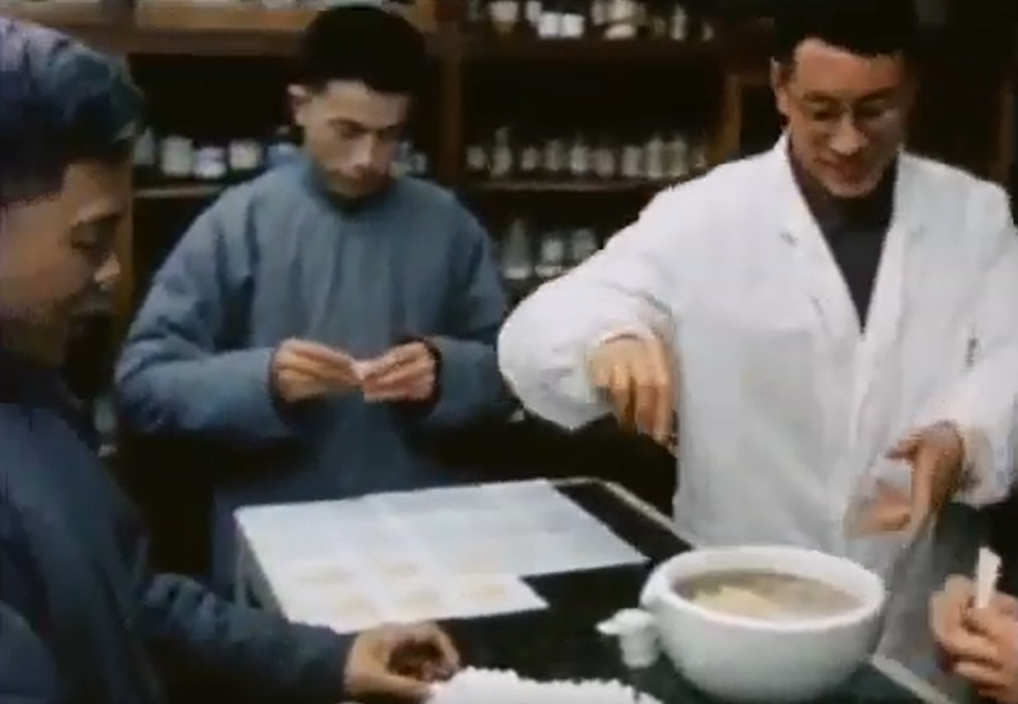

11 - The Pharmacy

Watch The Pharmacy on YouTube [01:15:24]

In this section, we spend time at a pharmacy in Shanghai.

Narrator: Medical care and medicine is free for the working people. Everything is paid for by their company. Those who don’t work have the same rights by paying 1 yuan annually. With a prescription one pays absolutely nothing. Without a prescription, one pays.

Interview with the Workers

A group of workers at the pharmacy are talking about the nature of their work and how it's changed since the Cultural Revolution.Employee #2: That’s what we call putting profits at the helm.

Manager: In my case, I was influenced by Liu Shaoqui before the Cultural Revolution. That was when our drugstore preferred to deal only with big orders. We used to encourage the consumption of expensive medicines and stimulants. We were always eager to handle the big deals. Small business had no interest for us.

Interviewer: Do you get a bonus as well as your salary?

Manager: Bonuses no longer exist. Bonuses used to depend on the profits of each enterprise. They increased along with the profits.

Employee #1: I was only interested in my bonus. As soon as my bonus was in sight, I cared only for the bonus - not for the people.

Employee #2: We’re the ones who criticized you - you the managers. But when we questioned your attitude, in fact, we were putting ourselves on trial.

Manager: It used to be very simple before. I gave orders and the workers obeyed me. That didn’t encourage them to use their own initiative. Collective management might seem to take more time. We have to discuss, get together… all that takes time. Before the CR, I made all of the decisions alone. Now we talk everything over and encourage personal initiative.

Employee #3: Before, you practically never consulted anyone. Since you never listened to us, well, we finally kept quiet.

Employee #2: One single person managed everything and that person was the only one who had the right to make himself heard. If I’m asked to speed up the work because a lot of people are waiting, I can think about it and hurry. But if I’m ordered to hurry, I just couldn’t care less. And that brings us to a dead end.

Manager: I used to think: the leaders have entrusted me with a specific job. I have to carry out their orders, step by step as they want. In other words, I reacted like a robot. That’s why my conduct was criticized by others. They said I was being too servile.

Employee #2: Before the Cultural Revolution, it was a privilege to voice an opinion. We condemned that attitude. Today everybody can speak their minds. Today the leaders do the same work as the other employees.

Manager: I wait on the customers, since the drugstore is open day and night. I also work the nightshift. In other words, we do all the same studies, the same work, and perform the same services.

At one point, an angry customer comes in. He's frustrated and nearly shouting at the workers about a throat spray he bought. He claims the spray bottle doesn't work. The workers try to calm him down, and agree to look at it with him. Together, the workers and the man take a look at the spray and manage to get it working again.

Interview with a woman employee

Employee: When I started to work in the drugstore, at that time, I didn't like the work they made me do. I used to think only the doctors performed a service worthy of respect and I only did the work of a servant. That's why I wasn't happy with my career. I wasn't interested in politics or in political studies. I only had one idea in mind: that was to become a doctor. That was my only goal.

It was only after the Cultural Revolution that I started asking myself this: Does one try to become competent in order to become famous or to serve the people? In fact, you must become competent in order to serve the revolution. I understood the real importance of the idea of serving the people and how to serve them.

[...]

Interviewer: Do you think that women's liberation is a reality in China?

Employee: In principle, I can say the problem has been resolved. Women are no longer victims as they were under the old regime, subject to marital and religious power. There might still exist inequality from certain couples - women in China are not 100% liberated. We still need some more time to get to that stage.

Interview with the former owner, Hong

Narrator: Under the old regime, this salesman Hong was a jeweler. When the jewelry business wasn't doing well, he turned to pharmaceutical work. He is the former owner of the drugstore.

Interviewer: What exactly does your work consist of?

Hong: I'm an employee, and as an employee I work at all the different aspects of this business.

Interviewer: Your salary is higher than that of the other employees. Why is that? Do you find that normal?

Hong: No, it's not normal. I make the same wages as I did in the days of private enterprise. The state hasn't reduced my salary. My comrade workers and employees who do the same work as I, make at most 82 and a half yuans while I earn 107 yuans.

Interviewer: Do you participate in the management of the drugstore?

Hong: Before, I used to participate, but, since I'm an old capitalist, my thoughts aren't always well-adapted to the socialist system. And for that reason, when it comes to administrative problems, I don't always adapt very well. For example, the problem of inventory: well, I like to have a big stock on hand. I like things to move easily. It's better for a business. But that's a bourgeoisie idea. Workers and employees don't think the same way, therefore I think it's better that I don't participate.

Worker/Peasant Control Committee

Narrator: The drugstore has set up a worker/peasant control committee. Three neighboring factories including this pharmaceutical company send their elected representatives. The neighborhood also sends a delegate. This kind of joint control between customers and employees is still unusual. It is still an experiment.

The scene cuts to the representative talking to her coworkers in the pharmaceutical factory.

It cuts to a few other workers coming to the representative with further criticisms or requests from the pharmacy.

Then, it changes to the view of the peasant representative. She goes around, asking the other farmworkers for any special requests or criticisms for the pharmacy before their meeting.

The meeting that follows is also documented, and shows many people sitting around a table, including both representatives. Each representative brings up the concerns, which are openly discussed around the table.

By discussing these concerns openly, they're able to come to an agreement about how to resolve the issues.

12 - A Woman, A Family

Watch A Woman, A Family on YouTube

Grandmother: I was 8 when I became engaged. My father had no money, so he went to see his cousin to borrow a pig. He sold the pig to get some money, but then he couldn't pay back his cousin. So he said, 'here, take my daughter instead'. His daughter for a pig! My father said, 'take my daughter and we will be even'. His cousin said 'all right, we'll forget the 8 yuans for the pig'.

[...]

Feet were bound up very tightly, and the bindings were sewn up. Binding was part of our oppression. I cried a lot, but they forced me. It was very painful. I had to learn on something in order to stand up. I couldn't even walk.

Interviewer: At what age was it done?

Grandmother: Around 6 or 7. Now it's all over. It's wonderful. In those days, in spite of our tears, they would bind tighter and tighter. Our feet were deformed. They would get infected. The toes were crushed together, bones were broken, it was unbearable.

If you had big feet, no man would marry you. Before taking a wife, a man would look at her feet. On the wedding day, when the bride arrived, everyone came to look at her, or rather at her small feet. They would admire her small slippers and their fine embroidery.

In the old society, people thought the more sons you had, the richer you'd get. People don't think like this anymore.

Father: Parents aren't always right. Children have the right to disagree. Family relationships are different now. We discuss politics.

Narrator: These are workers' children on the factory grounds. The factory is concerned with more than the production output of its 8,000 workers. It is concerned with the lives of its 40,000 people.

Some workers live far away. Many young people prefer not to live at home with their parents. Without waiting for the municipality to take the first step, the factory has decided to provide living quarters for them on its own grounds.